The Infamous Riot in Jefferson City, MO

During the years of 1953 and 1954 there had been a rash of prison riots across the United States. Many feared the Missouri system was ripe for an outbreak as well. The potential for riot became a popular topic of conversation which the Missouri Highway Patrol took very seriously, drafting a plan and training officers how to respond to such an event. The advance preparation would come in handy before long.

The Brewing Storm

It was Wednesday evening, September 22, around 6:30, when two inmates feigned illness to attract the attention of two guards. When the guards entered the hall to investigate, they were overpowered and their keys were stolen. One of the guards was beaten severely. The two convicts then bolted out of their cell and ran along the cellblock, releasing others as they went. Soon a large group of inmates was running loose, racing around the compound and emptying other cellblocks along their path. One group of inmates entered the dining hall, smashing windows and chairs. In the prison shops, anything flammable was set afire.

Highway Patrol Gets the Call

Missouri Highway Patrolman Walter Wilson was eating dinner in his patrol car when he heard an urgent message come over his radio; “Proceed to Jefferson City at once, prison riot in progress!” Obeying the riot plan procedures, he immediately headed towards Jefferson City. Simultaneously, other patrolmen from all over the state turned their cars toward the capital city as well.

By midnight, more highway patrol troopers, Kansas City and St. Louis police, national guardsmen and local police had surrounded the prison. Inside, several hundred convicts were running, shouting and throwing bricks and chunks of concrete at the deputy warden’s office. Four buildings were fully ablaze and more fires were being started. Soon, nearly 2,500 rioters were on the loose inside the walls. In this chaotic nightmare of activity, one inmate in solitary confinement was tortured and murdered by other prisoners.

Convicts Rampage Through the Night

Trooper Wilson and the other highway patrolmen continued their vigil throughout the night, as the law enforcement groups tried to prevent a mass breakout: “As waves of rioters stormed the deputy warden’s office, armed troopers on the roof were finally forced to open fire with machine guns and riot guns to force the desperate prisoners to flee the prison yard. Several convicts were injured by gun fire,” Wilson later wrote.

Officials Regain Control

Confronted with that mighty show of firepower, the inmates were finally forced back and most scattered to take cover wherever they could. Officers finally gained control, flushing out small groups of men and subduing the group of ringleaders. Another 300 prisoners were still barricaded in B and C cellblocks, cornered but not ready to surrender. The law enforcement officers left them alone and retreated, while in the warden’s office a meeting was held to decide how to handle the situation.

The assembled members of the press were told that no attempt to secure the cellblocks would take place that night. Governor Phil Donnelley, Lt. Governor James Blair, Director of Penal Institutions Thomas Whitecotton, Warden Ralph Eidson and Highway Patrol Superintendent Hugh Waggoner had been at the riot scene since it began and were growing weary. At last they announced that all troopers were to meet at 7:00 the next morning, when they would be given instructions on how to enter the building. It was a sleepless night for the law enforcement teams.

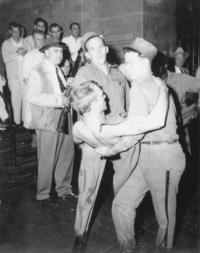

Troopers Storm the Grounds

245 troopers attended the next morning’s meeting. 18 men were chosen to lead the way into the cellblocks where the cornered rioters were in a forbidding four story white stone building. Trooper Wilson was one of those 18 selected. 100 St. Louis police officers and the remaining troops would stand outside the prison yard as a second wall of defense. These officers were also to process the 300 convicts, if and when they were taken captive. Wilson writes that this moment was the crucial one, when all of his training as a trooper would be put to the test:

“It was a tense moment and anything could happen: we were heavily armed with riot guns and submachine guns as we entered the massive building. The inmates inside were shouting, cursing and throwing articles of bedding, furniture and personal belongings. All the windows had been broken out. As we entered the door we were greeted by flying debris. A 50-lb cake of ice pushed from a tier above barely missed my head. As we plunged through the hallway, wading in four inches of water I noticed to my left that the water in front of one cell was crimson red. Red with the blood of one of the wounded convicts who had been stabbed earlier by a fellow inmate. Over the loud speaker, the convicts were ordered to get into the nearest cell and be quiet or they would be shot. One inmate ignored the order, leering and shouting. Without hesitation, one of the troopers raised his weapon and shot the troublemaker dead. At that, an eerie silence fell in the huge building. The convicts retreated into the nearest cells as instructed and the troopers slammed shut and locked the doors behind them. Up to nine prisoners were crammed into the tiny cells. When all were safely locked away, an all-clear whistle sounded. Then, one cell at a time, the men were strip searched, taken out into the yard and processed by the waiting officers. They were returned to their proper cells. It took until mid-afternoon to finish the job.”

Facts Get Sorted Out

When the riot was all over, four inmates had been killed, 50 injured and one attempted suicide. Four officers had been injured. Burned out hulks of several buildings lay smoldering. Damage was estimated to be as high as $5 million dollars. Not one prisoner had succeeded in escaping the prison. No attempt was made to serve breakfast to the prisoners the next day. Instead, they remained locked in their cells and sandwiches were handed out. The evening meal, usually served at 4:30, was served at 3:00. Small groups of convicts, with hands clasped behind their heads, were marched to the dining hall. 85 troopers stood with weapons ready to prevent further violence.

It was later reported that the majority of the black inmates had not participated in the riot and had remained in their cells throughout the ruckus. A schoolteacher at the prison gratefully credited two of his convict students with saving his life during the uprising.

Governor Donnelly Acts

The day after the riot, Governor Donnelly ordered a massive shakedown of the entire prison. 100 St. Louis policemen joined with prison guards to search every corner of the giant Penitentiary for knives, homemade weapons and other contraband. The search revealed an enormous arsenal of weaponry: sledgehammers, axe handles, screwdrivers, scissors, files and pieces of heavy machinery filed down to sharp, deadly points. Two days after the riot, Governor Donnelly grimly toured the ruined areas inside the prison.

When he emerged, he announced that convening a special legislative session would probably not be necessary, as he felt repairs could be made with funds already on hand. Meanwhile, the prisoners were complaining to the press that one of the major causes of the riot had been dissatisfaction with the newly appointed Parole Board. Three members had been appointed just weeks before the riot, and all were former members of the Highway Patrol. The inmates claimed that these former cops, as they referred to them, would not be impartial when the time came for parole consideration. During a press conference held the Monday following the riot, a reporter asked Governor Donnelly if he planned any changes in the Parole Board as a result of the prisoners’ complaints. “No sir,” Donnelly replied irritably, “I’m not going to let a bunch of convicts tell me what to do.”